Can Terror Armies Be Tactically Defeated Through Ground Maneuver? "Iron Swords" War as a Case Study – Gal Perl

To read the research in PDF format click here

Abstract

During the “Iron Swords” War, it was repeatedly reported that the IDF had tactically defeated Hamas military formations and territorial strongholds – only to soon find itself compelled to return and fight over them again. This raises a fundamental question: can terrorist armies be tactically defeated through ground maneuver, and if so, how? The IDF achieved impressive operational achievements during the war, defeated Hezbollah, and even reached the brink of strategic victory in the Iranian theater. However, a significant ground effort aimed at tactically defeating a terrorist army took place only in the Gaza Strip (in Lebanon, the ground maneuver remained a secondary effort). An analysis of this campaign suggests that defeating a terrorist army requires a combined approach which merges the principles of defeating industrialized armies – through a deceptive maneuver that destabilizes, unbalances, and rapidly collapses their systems – with a prolonged and systematic counterterrorism campaign, once the enemy has fragmented into small terror cells.

Introduction

During the “Iron Swords” War, it was repeatedly reported that the IDF had tactically defeated Hamas-controlled formation and areas, only to find itself compelled to return and fight over them once again. For example, in September 2024, the IDF declared that its forces had defeated the Rafah Brigade (Levy, 2024), yet by April 2025, it acknowledged the need to resume operations against Hamas’s Rafah Brigade, as it had not in fact been defeated (Zohar, 2025).

A similar case occurred in the town of Beit Hanoun. The IDF targeted Beit Hanoun at an early stage of the war. Division 252, under the command of Brig. Gen. Moran Omer, was assigned to attack the town from east to west – both as a deception maneuver based on Hamas’s expectations (according to the IDF's perspective) and in order to remove the threat Beit Hanoun posed to nearby Sderot. The division was reinforced with the reserve armored brigades 10 and 14, the Negev Brigade (12), a reserve infantry brigade composed of former Giv’ati soldiers, and the reserve commando Brigade “Fire Arrows” (551).

At midnight on October 28–29, 2023, forces from 551 Brigade crossed the border fence from Kibbutz Erez into the Gaza Strip, advancing on foot along a three-kilometer route to Beit Hanoun. The reserve Paratroopers Battalion 697 spearheaded the movement (disclosure: the author fought within this unit during the "Iron Swords" War), supported by D9 bulldozers and an attached tank company. At first light, the battalion attacked the outskirts of the built-up area, established a foothold, and was followed in sequence by the rest of the brigade. Its forces killed Hamas operatives, destroyed terror infrastructure, weapons caches, command posts, fighting positions, and tunnels. In parallel, the Negev Brigade operated in a separate sector of the town, while the 14 Brigade captured the “Palestine” outpost near the border fence. After approximately two weeks of fighting, 551 Brigade was deployed to combat in Beit Lahia. Anyone who had seen the battlefield in Beit Hanoun firsthand could hardly imagine that intense combat would again be necessary there a year later. And yet, IDF forces such as the Nahal Brigade, returned to fight in the town in August 2024 and again in January 2025, engaging the enemy and sustaining casualties (Levy, 2025).

Conversely, a series of analyses suggest that while Hezbollah was decisively defeated, Hamas was defeated only as a terrorist army (and then has shifted to guerrilla operations), and that recently, during Operation “Rising Lion” conducted in Iran, Israel succeeded in bringing Iran to the brink of decisive defeat. In the past, the IDF successfully defeated regular armies in several conflicts – whether initiated by Israel (as in the Six-Day War) or imposed upon it (as in the Yom Kippur War) – as well as terrorist organizations (e.g., the expulsion of the PLO from Beirut to Tunis during the First Lebanon War and the defeat of Suicide bombers Terror during the Second Intifada). Yet over the years, as threats evolved, the IDF's ability to achieve tactical-level decisive acts against terrorist armies has changed, raising the question of whether such organizations – like Hamas or Hezbollah – can be tactically defeated in Gaza or in Lebanon.

The broader concept of decisive victory (at the strategic and operational levels) – and its distinction from related terms such as "victory" and "surrender" – lies beyond the scope of this article, as do the strategic decisive victories achieved by the IDF during the "Iron Swords" War in other theaters through airpower alone or with limited ground support (although these will be mentioned). However, it seems appropriate to examine whether and how terrorist armies can be tactically defeated through ground maneuver, using the IDF’s combat operations in the Gaza Strip during the “Iron Swords” War as a case study.

What Is “Decisive Victory” and What Constitutes Tactical Decision on Land?

A military decision in war is defined as the “denial of the enemy’s capacity to continue fighting during a war, on the battlefield, by military means, such that recovery within the framework of the same war is highly unlikely” (Kober, 1996, pp. 25–26). The enemy’s fighting capacity consists of two components: will and capability. Will refers to commitment, motivation, fighting spirit and determination, while capability refers to the combination of means and skills available to the state to conduct military conflict on the battlefield. A decline in various components of capability – whether in command and control, technology, or force structure – directly affects the will to initiate or continue warfare. This creates a dynamic of collapse (Kober, 1996, p. 26). It is important to emphasize that decision is, first and foremost, a matter of a mental state. As Colonel John Boyd of the U.S. Air Force stated: “Machines don’t fight wars. Terrain doesn’t fight wars. Humans fight wars. You must get into the minds of humans. That’s where battles are won” (Shelah, 2003, p. 41).

In the IDF Ground Forces’ doctrine, at the tactical level, decision is defined as bringing the enemy to a state in which it is incapable of acting effectively against our forces, thereby imposing our will upon it. The tactical dimension of this definition is achieving a position of advantage that neutralizes the enemy’s effectiveness (IDF Ground Forces Command, 2012, pp. 17, 50). The doctrine outlines two approaches to achieving such a decision:

- The Maneuver Approach – The Maneuver approach is fundamentally based on deception. The attacker must locate, create, or exploit a weak point to induce shock in the enemy, rendering it unable to recover and causing its collapse. The maneuverist approach requires optimal understanding of the enemy – its disposition, critical assets, centers of gravity, and vulnerabilities – in order to exploit them toward its defeat. “The maneuver approach requires granting significant autonomy to each commander and unit, and decentralizing command and control – what is known as ‘mission command.’ This is necessary because the pace of battle and its shifting conditions will not always allow subordinate commanders or other key personnel to receive directives regarding the appropriate course of action in the various combat scenarios they may encounter. It is also intended to enable them to seize emerging opportunities on the battlefield (IDF Ground Forces Command, 2012, p. 65).

- The Attrition Approach – The Attrition approach relies on the systematic destruction and degradation of enemy assets with the aim of wearing them down until they can no longer operate effectively. Decision is achieved by the methodical elimination of enemy personnel and assets until too few remain to mount a defense or offensive (bearing in mind that “attrition is always mutual”) (IDF Ground Forces Command, 2012, p. 66).

Traditionally, the IDF has preferred the maneuver approach due to its potential to shorten campaigns by implementing principles of war such as deception, force optimization, and concentration of effort. Maneuver demands deceptive action but also a high operational tempo across all enemy systems, in line with the principle of continuity, in order to defeat the enemy rapidly. Maneuver power depends on momentum and must include firepower and mobility. Tempo is shaped by seven interrelated factors: physical mobility, tactical rate of advance, volume and reliability of information, logistical and combat support, duration of movement completion, command and control, and communications. Failure to meet these conditions enables enemy recovery (Simpkin, 1999, pp. 60, 152).

A recent example of such a ground campaign can be seen in the outbreak of the “Iron Swords” War, when Hamas launched a deliberate, surprise attack grounded in deception. The operation demonstrated a clear understanding of the IDF’s centers of gravity, strengths, and vulnerabilities. Hamas concentrated its efforts on neutralizing the IDF’s advantages, exploited its weaknesses, and ultimately achieved a tactical defeat of the Gaza Division (Bazak & Gilat, 2024). Hamas possessed clear advantages in force size and weaponry, as well as the inherent benefits of initiative and surprise. Moreover, the deceptive plan that Hamas executed was based on timing – taking advantage of a period of low alert and limited force deployment due to the holiday – and on a strategy of lulling the IDF by refraining from offensive initiatives during previous periods of tension and conflict, so as not to expose the forthcoming assault plan.

On the morning of October 7, 2023, the offensive began with a massive barrage of rockets, missiles, and mortars. Under this cover, Hamas operatives disabled surveillance cameras and observation systems – some via suicide drones – as well as generators and communications systems, aiming to “blind” the IDF. Simultaneously, hundreds of Hamas’s elite Nukhba fighters, traveling on pickup trucks, motorcycles (and even motorized hang gliders), approached the border armed with explosives, heavy engineering equipment, and weapons. They breached the border at dozens of points (Dvori, 2023). Then they proceeded to attack border outposts – essentially camps that were difficult to defend and offered no protection to their surroundings (Hazut, 2024, p. 333). Among other targets, the Nukhba fighters stormed the Gaza Division headquarters at Re’im base and neutralized it. Furthermore, while the first and second waves of Nukhba operatives raided Israeli border communities, the planners – who had anticipated IDF reinforcements – attempted to seize strategic junctions to ambush incoming Israeli forces. The result: a massacre on the border communities and, more critically, the defeat of the Gaza Division.

Terrorist Armies – Defining Characteristics

Since the early 2000s, the nature of military threats facing the State of Israel has evolved. On the one hand, threats from industrial armies – such as the Syrian army under the Bashar al-Assad regime – persisted for years, though the risk of invasion and territorial conquest decreased. On the other hand, the severity of missile and rocket fire threats from sub-state and quasi-military organizations such as Hamas and Hezbollah sharply increased (Eizenkot, 2010, pp. 23–32). A further development was the transformation of these organizations, as defined by the IDF, into bona fide terrorist armies through an evolutionary process whereby terrorist groups formalized, consolidated, and adopted various military characteristics. This has manifested in a military-style organization with advanced weaponry (including an extensive rocket arsenal), the establishment of hierarchical command and control structures, defensive preparations featuring positions, command posts, and bunkers, and the creation of maneuver capabilities exemplified by Hezbollah’s Radwan units intended for the conquest of the Galilee and Hamas’s Nukhba forces (Kochavi, 2019).

Above all stood Iran, a sponsor and trainer of these terrorist armies (and other militias), as well as a state developing a military nuclear program and a ground-to-ground missile system that threatened the Israeli rear (Hendel & Katz, 2011, pp. 80–82, 187–188). Although the Northern Command invested significant effort in preparing for the possibility that elite forces might be employed in surprise attacks aimed at capturing positions and settlements near the border fence (Baram & Perl Finkel, 2021, pp. 8–9), the Southern Command – and especially the Gaza Division – were unprepared for a large-scale invasion, and its defensive array collapsed at the outset of the assault (Kubovich, 2025).

In discussing how such terror armies are defeated, it is first necessary to examine their principal characteristics:

- Non-Adherence to Conventional Doctrine. In force planning and development, a terror army formulates a combat doctrine tailored to the operational environment and nature of warfare it is expected to face, without insisting on concepts irrelevant to its context

- A rapid transition from a military appearance – uniforms, vests, and helmets – to a civilian look that enables blending into the population. Fighters who previously sported uniforms, body armor, and helmets – and appeared in propaganda videos as skilled commandos operating advanced military equipment – do not hesitate to abandon all military traits and don civilian attire to blend into the population for survival, concealing weaponry in operational apartments, tunnels, and bunkers via a “drop and use” method.

- The process a terror army undergoes during intense fighting with a superior enemy is markedly different from that of a regular industrial army. When industrial, regular armies – driven by state logic and guided by national intent – sustain a crushing and decisive blow, they tend to collapse and lose the coherence of their operational logic. In contrast, when a terrorist army absorbs such a blow, it does not break apart in the same manner; rather, it disintegrates into its basic components – individual terror cells.

- Another systemic trait, especially among Middle Eastern terror armies and arguably their supreme strategic expression, is their refusal to cease fighting as long as they can continue. Terror armies are committed to the concept of “resistance”, even if success is delayed beyond their lifespan, as they are “planting carob trees” (Col. G, 2024, p. 42).

- At the tactical level, several features encountered by the IDF challenge the ability to decisively defeat a terror army: a vast quantity of weaponry dispersed throughout the battlefield (not “attached” to forces as in regular armies); extensive underground systems that dramatically impeded the ability of maneuvering forces to gain advantageous positions over the enemy.

The 9263 Paratroopers reserve battlaion during a raid on a weapon's cache in a village in south Lebanon in the "Iron Swords" war. (IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

So, how can a Terror Army be Decisively Defeated at the Tactical Ground Level, If at All?

From the above, it is clear that decisively defeating terror organizations or terror armies at the tactical level is not an event achievable in six days, nor within a short timeframe similar to that in which IDF forces crossed the Suez Canal and encircled the Third Army during the Yom Kippur War (19 days of pure combat). The former U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Michael Mullen, stated that "success in this type of war will always be protracted, not decisive. There will be no single day when we stand and say, 'It’s over. We won.' We will win, but only over time and only after a continual process of reassessment and adaptation. Honestly, it will not feel like someone who just delivered a knockout blow, but rather like someone recovering from a long illness" (Shelah, 2015, p. 79).

Accordingly, no one can point to an agreed-upon date marking the end of the Second Intifada. Some view the disengagement from the Gaza Strip in summer 2005 as the campaign’s finale. Others consider the completion of the Separation Barrier about a year later, which significantly hindered terrorists’ ability to carry out attacks inside Israel, as the endpoint. Some see it as a combination of both, while others mark 2007 as the year when suicide terrorism waned. Regardless, it is apparent the process took a considerable time. Operation "Defensive Shield" (March 2002), during which IDF forces operated for about a month and a half in several cities across Judea and Samaria (Harel & Issacharoff, 2004, pp. 235–269), was a pivotal point, but it did not decisively end the campaign; rather, it created the conditions to restore operational control of the area, which in turn defeated suicide terrorists in the Second Intifada (Siboni, 2010, p. 96). It should be noted that during the operation, except for an ambush in the Jenin refugee camp, forces encountered almost no organized resistance from terror organizations and fought primarily against cells, gangs, and individuals (Drucker & Shelah, 2005, p. 219).

Following the operation, a “lawn mower” campaign was required – during which Judea and Samaria Division commanders led numerous raids and operations deep within Palestinian cities (Drucker & Shelah, 2005, p. 348). “Against suicide terrorists, guided missiles, and rocket fire, one can fight effectively only by controlling the territory”, stated the then-division commander Gadi Eizenkot, a Golani Brigade veteran. Under this approach, armored forces were significantly reduced in the area, replaced by special forces and elite infantry maintaining a permanent presence and conducting continuous raids deep within Palestinian cities. These raids relied on precise intelligence and emphasized strict discrimination between militants and uninvolved civilians (Shelah, 2005, pp. 8–9). Eizenkot’s successor, Yair Golan, a former paratrooper, continued this approach over the following two years, noting at the end of his tenure that IDF Forces “operate in all camps and refugee camps. For example, Hamas’s infrastructure in Nablus was dismantled down to the last operative, all thanks to operational freedom” (Weiss, 2007). This approach drove Palestinian suicide terrorism out of Judea and Samaria and effectively suppressed the Second Intifada.

The IDF Ground Forces doctrine recognizes this reality. Given that irregular forces (terror and guerrilla) are, by nature, based on their ability to wear down and exhaust their enemies over time through small-scale actions, it states that one of the best ways to defeat them is by maneuvering deep into the territory from many different, opposing, and simultaneous directions so that forces reach the enemy’s hideouts, destroy their assets, and kill their operatives. For this purpose, one does not occupy the entire area, but rather key controlling areas from which continuous (the key word) raids are launched against enemy outposts and hideouts, aiming to harm operatives and wear down enemy morale until decisive victory (Ground Forces Command, 2012, p. 67). The raid method is very effective in such a campaign, as it is deceptive in nature – both systemically and tactically – and because it makes it difficult for the enemy to anticipate IDF actions and prepare accordingly. Raids, during which maneuvering forces enter enemy territory, strike, and then return to our lines, allow forces to surprise the enemy, avoid predictability, undermine the enemy’s confidence, and create a feeling of pursuit. This is especially effective against terror armies like Hamas and Hezbollah, as they are prepared to defend against certain directions of attack, are inferior to the IDF in intelligence and real-time control capabilities and generally avoid counter-maneuvers that would expose them to IDF’s firepower and maneuver capabilities (Shelah, 2015, p. 122).

Furthermore, it is worth noting a distinction made by Brigadier General (res.) Moshe (“Chiko”) Tamir, former commander of the Golani Brigade during the Second Intifada and later of the Gaza Division, when describing how combat was conducted in the Jenin refugee camp before and during Operation “Defensive Shield”. He stated, “The complexity of the situation and conditions on the ground required repeated entries into the camp to cleanse it of hostile activity. Each IDF entry only covered a portion of the camp, while terror cells moved and continued to operate from other areas. It is similar to fluid movement within a closed system – a single point of pressure causes the fluid to move away from that point. Only effective pressure on multiple points will drive the fluid to the center” (Tamir, 2012, p. 4).

It appears that terrorist armies are defeated through a combination of defeating industrial armies by means of a deceptive maneuver that destabilizes, unbalances, and rapidly collapses their systems, alongside Sisyphean, systematic fighting against terror once the terror army fragments into small terror cells. This stage cannot be skipped and must be completed before moving to the stage of decisively defeating the remaining terrorist and guerrilla cells. To defeat these terror cells requires enclosing them within a confined area, hunting them down (Mattis & West, 2022, p. 122), and continuing to close in on them by denying any shelter, protection, or safe space. Both stages require intense, close fire support, with tight coordination and short sensor-to-shooter cycles, in order to support the forces in demolishing structures used by the terror army and its operatives, and to engage fleeting targets with short time-on-target (Finkel, 2024, p. 34). This also includes extensive use of combat engineering units to destroy terrorist infrastructure and subterranean systems.

At the same time, it is necessary to drive a wedge between the terrorist forces and the local population that provides them with cover, concealment, assistance, and a recruitment base – by offering that population an alternative through a coordinated civil and security system. This requires a combination of vigorous and focused military action that targets only terrorist operatives or members of the terror army, while minimizing, to the greatest extent possible, harm to non-combatants (not only because this is the more moral course of action, to strike the enemy and only the enemy, but also because such harm undermines efforts to engage the local population and tends to unify it around the terrorist elements) and a mix of social and political instruments (Tovy, 2009, p. 77).

Years later, former Deputy Chief of General Staff Maj. Gen. (res.) Yair Golan stated that defeating terror armies requires three actions: “First, to kill as many of them as possible; second, to destroy as much of their weaponry as possible; and third, to destroy the maximum amount of their operational infrastructure” (Golan, 2019). Moreover, given the nature of terror armies which transform from organized forces into dispersed terror cells, the imperative becomes even stronger to follow the logic articulated by then-Chief of General Staff Shaul Mofaz, who argued that victory consists of “small tactical victories; defeating the enemy at every point in every encounter” (Mofaz, 2024, p. 215). This insight is sound (and perhaps unsurprising, considering Mofaz adhered to this principle since his days as a squad leader in the Paratroopers, through his role as brigade commander during the Meidoun operation, and later as IDF's Chief of the General Staff during Operation Defensive Shield). However, achieving victory in every encounter and dismantling above and below ground terrorist infrastructure takes time – a great deal of time.

While the doctrinal literature does not spell this out explicitly, a review of historical writing reveals the components that have been used in the past to achieve tactical-level victories. These will serve as a basis for comparison with what transpired during the Iron Swords War:

Soldiers of the elite "Shaldag" unit during operation "Many Ways" in Syria) (Image by the IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

The "Iron Swords" War – What Happened There?

Most of Israel’s wars until the Yom Kippur War were multi-theater conflicts, requiring the IDF to fight simultaneously on several fronts, whether coordinated and mutually supportive or not. To address this challenge, Israel implemented the approach of ”operational decision through strategic grading”. That is, “once war was forced upon it, Israel removed the threat by dismantling the coalition of Arab states through a military decisive victory one army after another. This had operational manifestations on land, in the air, and at sea” (Peleg, 2023, p. 37). The most severe multi-theater war before “Iron Swords” was the Yom Kippur War, in which Israel was attacked simultaneously from north and south, forcing it to divide its forces. Since then, most conflicts involving Israel have been single-theater.

In many ways, Israel adopted – whether consciously or not – the approach of operational decisive victory applied in an "operational decision through strategic grading” in the “Iron Swords” War as well. After repelling Hamas’s initial surprise attack on October 7, 2023, and a short preparation period (three weeks), the IDF launched an offensive against Hamas in the Gaza Strip aimed at toppling Hamas’s rule, destroying its military capabilities, and creating conditions to recover hostages (Cohen, 2023). This effort, for the first time in many years, incorporated a substantial ground maneuver and an aerial campaign that provided close support to ground forces, alongside targeted elimination operations – including the killing of senior Hamas operatives Marwan Issa and Mohammed Deif (Hazut, 2024, pp. 342–373). It is nevertheless worth asking: how long did this campaign last, and was there alignment between the resources allocated to it and its objectives, such that those objectives could be realistically achieved?

Simultaneously, the IDF conducted defensive operations on the northern front against Hezbollah, reinforcing forces and evacuating many communities in the Upper Galilee. For over six months, the army waged a protracted attrition battle of intermittent fire exchanges with Hezbollah, which, although refraining from ground attacks, persistently launched rockets, drones, and indirect fire at IDF posts, bases, and northern towns, aiming to divide the IDF’s efforts and prevent efficient concentration. The political directive was to avoid broad escalation due to the southern campaign. The situation changed in July 2024, following a rocket strike on a soccer field in Majdal Shams on the Golan Heights that killed 12 children and youths and injured 34 others. Until then, Israel feared the possibility of needing to launch an offensive in the north, but after this event, a decision was made for a harsh response, including the assassination of the organization’s military commander Fuad Shukr (Al-Hajj Mohsen), despite the risk of significant escalation.

From an external perspective, it appeared that under the command of Chief of General Staff Herzi Halevi, the IDF had “changed its tune” and begun conducting a cunning and surprising campaign against the organization. However, it did so gradually and incrementally, in a manner that prevented Hezbollah – like frogs slowly boiling in a pot – from fully recognizing the shift in approach (Hazut and Shelah, 2024).

This campaign was based on intelligence-driven, guided precision fire strikes designed to create systemic surprise across various targets and depths of intelligence penetration. Within about a month, most of Hezbollah’s leadership was eliminated through targeted killings of tactical and operational commanders within the organization, such as Ibrahim Aqil and commanders of the Radwan forces, the “This Is the Moment” Operation, which destroyed much of Hezbollah’s missile and rocket arsenal by aerial strikes, the “Pagers” Operation targeting communication devices executed by Mossad (Barnea, 2025), which were expressions of innovative and cunning thinking, the “New Order” Operation targeted Hezbollah’s headquarters from the air, killing the organization’s secretary-general, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, and a very limited ground maneuver in rally villages. All this without Hezbollah correctly detecting the operational transition Israel had made from defense to offense (Finkel, 2025, pp. 5–6). It should be noted that although Hezbollah considers itself the “Protector of Lebanon,” it is just part of Lebanon and its government, and evidently, other centers of power in the country pressured Hezbollah to end the campaign. This reality, combined with the fact that the IDF executed a very limited maneuver (not placing Hezbollah with its back to the wall), led Hezbollah to decide to stop the war.

At the tactical level, the maneuver in the “Northern Arrows” Operation was part of a larger whole. It seems that over the years Hezbollah became more of an army than a terror organization, neglecting its terror component. Hence, the campaign Israel conducted managed to topple it as it did the Egyptian army in 1973 and even in 1967. The severe blows delivered by the IDF and Mossad – severely damaging Hezbollah’s command and control systems, vital operational continuity networks, and offensive capabilities considered the core of its power – threw the organization off balance and decisively defeated it. After the Northern Command, under Maj. Gen. Ori Gordin, executed the ground maneuver in southern Lebanon on the night of September 30, 2024, the IDF divisions – including the 98th, the 36th, the 91st, and the 146th Divisions – crossed the border, maneuvered into rally villages, destroyed weapons, headquarters, bunkers, underground routes, combat positions, and struck Hezbollah operatives (Ben Yishai, October 10, 2024). It should be noted that rally village complexes were neutralized by division and brigade level fire, significantly reducing ATGM and guided missiles on the forces, while armored units were used minimally to reduce targets to the enemy. The forces managed to maneuver quickly relative to intelligence-identified combat infrastructure. However, it must be acknowledged that aside from a few exceptions – such as the battle waged by the Egoz Unit in the village of Al-Adaysseh (Zaitun, 2024) – the collapse of the organization was also evident in its general avoidance of direct engagement with IDF forces in most villages.

Following this, the IDF resumed the offensive in the south, operated in Rafah, and killed Yahya Sinwar in a clash near the Tel Sultan neighborhood (Ilani, 2025, pp. 22–33). Throughout, Israel maintained defensive operations in the Judea and Samaria front, Yemen, and Iran (including several offensive operations), and conducted a series of operations in Syria, the most prominent being “Many Roads”, a wide-scale raid by the elite Shaldag unit airlifted by helicopters to the center of Sers and a nearby underground factory producing Iranian precision missiles near the city of Masyaf in Syria, conducted on the night of September 8–9, 2024, during which the force killed Syrian soldiers and destroyed weapons and military systems at the facility (Col. B., 2025). In December 2024, the IDF was required to carry out a limited ground maneuver to seize the buffer zone and the Syrian Hermon region, in light of the collapse of the Assad regime (Ben Yishai, December 12, 2024).

In practice, during the war, Israel successfully balanced the various tensions and fronts, achieving impressive operational successes in all of them, prioritizing between theaters. This is not to praise the war management – like any war, there were mistakes and errors, such as the army’s desire to strike Hezbollah’s systems in Lebanon on October 11, 2023, instead of Hamas (Mofaz, 2024, p. 413). Yet, whether so or not, Israel’s direct actions (and in the case of the Syrian theater, indirect consequences) effectively removed the “ring of fire,” the bases of operation of the Shiite militias in Iraq, Yemen, Lebanon (Hezbollah), and the Sunni Hamas in Gaza, which were established and armed by Iran with rockets and missiles to deter Israel from military action against its nuclear program (Amidror, 2022, pp. 19–33). This created, in effect, a “window of opportunity” for action.

IAF Fighter pilot about to take-off on a strike in Iran during operation "Rising Lion" (Image by the IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

Indeed, in June 2025, after successfully stabilizing the security situation on the various fronts and faced with a strategic operational need, Israel launched Operation "Rising Lion," a wide-scale surprise attack on Iran. The operation, with its military component commanded by Chief of General Staff Eyal Zamir, included an extensive air campaign and covert operations through which air superiority was achieved, targeted eliminations of nuclear scientists, the "decapitation" of senior commanders and key figures in the Iranian security apparatus, attacks on headquarters and strategic facilities, nuclear sites, and ballistic missile sites (Zamir, 2025). Subsequently, the United States also joined the effort, providing assistance and support to Israel throughout the war, including international backing, arms supplies, missile and rocket defense assistance against attacks from Iran and Yemen, and conducting airstrikes on nuclear facilities in Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan (Ben Yishai, 2025).

The question naturally arises as to whether and to what extent Israel indeed chose to conduct the campaign according to the approach of “operational defeat, applied in an operational decision through strategic grading”. During the Yom Kippur War, Israel consciously adopted this approach (Peleg, 2023, p. 17). On the morning of October 9, 1973, Chief of General Staff Elazar explained how he henceforth envisioned the management of the war:

"If we want to win, it has to become worse for them than for us. Therefore, I want to divide them into two: there are the Egyptians and the Syrians, and I cannot hurt them both simultaneously. I need to take them one by one, and I must concentrate all the effort [...] On the Golan, the Syrians are in a worse position than the Egyptians. But the Syrians have two armored divisions, some more tanks in the rear, and I don't know how many losses the two divisions in contact have suffered. So now I need to take one enemy and break it, one – not both simultaneously. Of the two I need to break now; I want to break Syria [...] We must break Syria within the next 24 hours. Break it and then we will turn to Egypt” (Golan, 2013, p. 543).

Indeed, this is what happened. It is unclear whether a similar decision was made in the General Staff and the senior political echelon regarding the "Iron Swords" War, but one must admit this is the visible strategy, and the outcome is similar.

“Iron Swords” – So What Happened in the Gaza Strip?

Since a significant operational effort to decisively defeat a terror army on the ground occurred only in the Gaza Strip during the war, the analysis here focuses on this arena. On the night of October 26–27, in response to Hamas’s deadly terror attack, the Southern Command’s forces, both regular and reserves under the command of Major General Yaron Finkelman, launched a large-scale ground maneuver, the largest since 1982. The campaign’s primary objectives from the outset were to operationally defeat Hamas – that is, to eliminate its ability to raid and attack the communities surrounding Gaza and IDF forces near the border, and to decisively break its capacity to defend its territory. This entailed neutralizing its combat brigades as functional fighting formations, destroying as much as possible its ability to launch rockets and mortar fire toward Israel’s rear, targeting Hamas’s command and control systems and senior operatives, and dismantling supporting infrastructures. Only then will the conditions be created to allow for a transition to the area clearing phase.

The main effort in the ground maneuver was reflected in the attacks of the 162nd Division, commanded by Brigadier General Itzik Cohen, in northern Gaza, and the 36th Division, led by Brigadier General David (Dado) Bar Kalifa, which broke through the Netzarim corridor. These Divisions rapidly penetrated the heart of the Strip, understanding that Hamas had concentrated its defensive efforts on the outer layer, leaving the inner layer significantly weaker. The Divisions linked up on the coast and then moved eastward toward Israel. This was a maneuver designed to outwit Hamas, which had structured its defenses in the opposite direction, effectively denying Hamas the ability to fight efficiently based on its pre-war dispositions. Concurrently, the 252nd Division, moving from east to west and attacking Beit Hanoun, conducted a deception operation that misled Hamas about the direction and nature of the attack (IDF’s visual axis).

According to Brigadier General Moshe (Chiko) Tamir, who played a significant role in planning the campaign post-outbreak, the logic of the maneuver was evident in the encirclement of cities in the Strip, evacuation and population drainage (during which enemy operatives were also captured), and attacks contrary to enemy dispositions. The opposing system was dismantled through a combination of firepower targeting tunnels near the maneuver of ground forces into enemy territory – denying Hamas operatives refuge in the subterranean domain (“breaking coefficient”) – alongside a ground maneuver effort that exposed and killed Hamas operatives forced to remain above ground (Tamir, 2024). This logic was required given the nature of the enemy, and the IDF carried out various maneuvers (such as the capture of Gaza City) with much greater speed and efficiency than many Western armies in recent years. In most of the areas maneuvered by the IDF in northern Gaza, its forces succeeded in defeating the Hamas military formations arrayed against them. However, it was known from the start that with regard to the war’s objectives, territorial conquest and dismantling Hamas’s formations alone would not bring decisive victory. The enemy split into small cells operating guerrilla-style and dealing with them required sustained effort. Here, the lack of preparedness in force-building was evident, as the ground forces had been neglected for three decades in terms of resources and willingness to deploy them in various confrontations (Hazut, 2024, p. 63), and no appropriate action was taken accordingly.

At the tactical level, the IDF ground forces operated during the war based on a mission-oriented command approach, which is inherent in ground combat, and in accordance with this, the Southern Command managed the campaign (Finkelman, 2025). The forces displayed clever, bold, and unexpected thinking, manifested primarily in raids on Hamas strongholds. Among the notable raids on the southern front were Operation “Local Analysis,” a raid by the 162nd Division combined with special forces on the Shifa Hospital in Gaza, and Operation “Arnon” to rescue four hostages held by Hamas, executed by the Yamam unit with assistance from the Kfir, Givati, Paratroopers, and 7th Brigade forces in the Nuseirat refugee camp.

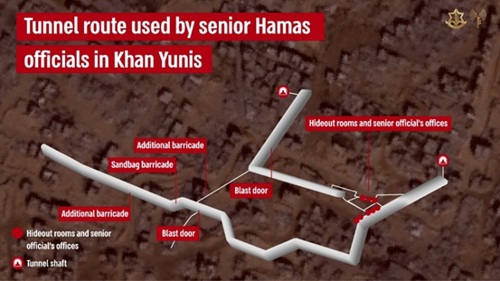

In Khan Yunis, the 98th Divison under Brigadier General Dan Goldfuss conducted a maneuver designed to surprise by rapidly advancing to the enemy’s core, sacrificing the security principle, and acting contrary to Hamas’s expectations. The operation began as a special mission tasked with locating and capturing or killing senior Hamas figures, with the brigade’s forces (about seven battalions) effectively protecting these efforts. The brigade fought a combined battle above and below ground, surprising the enemy with their willingness to fight in the subterranean arena, damaging Hamas operatives and destroying weapons and infrastructures (Goldfuss, 2024). However, the objective was not achieved. Despite operational successes, forces suffered losses and attrition in the grueling activity until they finally left the area. In May 2024, the IDF began operations against Hamas’s forces in Rafah. The fighting, which lasted about five months, was mainly led by the 162nd Division whose forces killed over 2,000 terrorists and destroyed many kilometers of subterranean routes (Levi, 2024). During this phase, the IDF killed Mohammed Deif, head of Hamas’s military wing, in an airstrike. In a clash with the battle team of Battalion 450, operating under the Gaza Divison commanded by Brigadier General Barak Hiram, near the Tel Sultan neighborhood, the movement’s leader, Yahya Sinwar, was killed (Ilnai, 2025, pp. 22–33).

However, it should be noted that since the IDF released most of its reserve forces in early January 2024, an effective operational pause in fighting occurred, followed by difficulties in maintaining momentum and initiative – both crucial for shortening the campaign. While it was clear the enemy’s interest was to prolong the war and even turn it into a prolonged multi-front war of attrition, the IDF sometimes acted predictably – causing damage to the enemy but prolonging the conflict with a logic of attrition. Moreover, the lack of sufficient force concentration, despite significant efforts and impressive command ability by the Southern Command in stretching its forces to cover and control the maximum possible enemy areas, caused the fighting described by Brigadier General Tamir in the Jenin refugee camp to repeat itself. In areas where the IDF did not maintain continuous operations, Hamas was able to recruit operatives (though far less experienced and skilled), partially replenish its ranks, and return to the fight. Perhaps the correct solution was to transition in areas where the IDF defeated Hamas’s military power to a method of area command maintaining a constant presence of ongoing security forces and creating an effective "lawnmower" that would prevent recovery. But this did not happen.

Ultimately, although the IDF effectively executed the crushing blow that broke the terror army, as described above, it struggled to decisively defeat the terror cells after the terror army fragmented due to the shelter provided by the extensive subterranean systems the enemy had built in advance, which allowed not only relatively safe shelter from IDF forces but also the ability to rearm and resupply and move between parts of the Strip. Destroying these systems is a slow and complex process primarily assigned to engineering and securing forces, which itself slows the duration and pace of operations. Conversely, the IDF’s ability to operate and fight in this domain, which developed and improved during the war, also created among Hamas operatives a sense of being hunted and undermined their pre-war assumption that this space was relatively safe.

Another factor was the shortage of manpower and resources necessary to clear the territory and deny the terrorists safe spaces. The size of the area and the extent of the enemy required large manpower commitments over time to maintain a continuous presence of forces to hunt the enemy. Time was exactly the resource over which the opposing interests of the regular army and the remnants of the terror army clashed. While one side sought to finish the task as quickly as possible, the terror aimed to prolong the campaign to drag the regular army into an attritional war that would wear down its forces and resources, as well as the internal and external legitimacy of the campaign.

The civilian component – an essential element in the shift from warfare against a conventional army to warfare against terrorism, whose goal is to drive a wedge between the terrorist infrastructure and the population – was implemented hesitantly and only partially. In practice, it largely amounted to humanitarian food distribution and the relocation of population groups from the north to the south in order to facilitate the ability to distinguish the enemy from among them, as the enemy remained embedded in the area. All these factors led to the IDF decisively defeating and dismantling most of Hamas’s brigades, yet these broke down into terror and guerrilla cells that continued fighting (Finkel, 2025, p. 5). It appears that from the summer of 2024, following the defeat of the Rafah Brigade, the Southern Command essentially began a prolonged phase of area clearance, destruction of terror infrastructures, and combating the remaining guerrilla cells. It can be estimated that this transition from warfare with an army to area clearance and counterterrorism contributed to Hamas’s agreement to a ceasefire in January 2025.

It should be noted that unlike Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas is the sovereign in the Gaza Strip, which, as stated by Major General (res.) Giora Eiland, is a de facto state (Eiland, 2018, p. 395), fully responsible for and controlling it. This is yet another reason, alongside the commitment to the idea of “resistance,” why its operatives refuse to abandon the struggle. In light of the IDF’s successes in ground maneuvering, Hamas found itself backed into a corner. Nevertheless, the movement did not relinquish its terror component, and although defeated as an army, it continued to operate in terror and guerrilla cells.

IDF soldiers fighting in the Gaza Strip during "Iron Swords" War (Image by the IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

Insights and Questions

From all the above, a few insights and questions emerge. First, decision (victory) is only one level in the act of war – a military decision pertains to the dynamics of fighting between armies and its outcomes on the battlefield, and as such reflects the military capabilities of the warring parties. Military decision is not necessarily the end of the war. Moreover, decision is always temporary. If it is not leveraged at levels above the tactical, it alone will not bring victory, and the enemy will not remain down for long. Its achievements will be offset. Following this, the clearest indication that Hezbollah and Hamas were decisively defeated as military formations is the fact that during the campaign in Iran they did not operate in accordance with the "Ring of Fire" plan. Hamas due to its reduced capabilities to residual levels, and Hezbollah due to its military defeat and choice to remain out of the campaign.

Second, there is a battle over time and interests between a regular army and a terror army that has become terror: the regular army closes every opening for terror through ambushes, raids, and destruction of infrastructure (but this takes time). Over time, the army’s forces erode (due to the Sisyphean nature of the operation and guerrilla actions against it), as does the internal and external legitimacy. And this is precisely what terrorism relies on. Hamas’s decentralization of power, its descent into underground infrastructure, its concealment within the civilian population, and other such measures are all designed to ensure its survivability – thereby prolonging the campaign. This strategy rests on the understanding that Israel will eventually face resource constraints and growing frustration stemming from its inability to achieve a swift victory (Ashkenazi, 2024).

Third, when examining decision at the tactical level, it must be redefined for each mission – there is a direct link between the concept of decision and the mission and the operational achievements defined for it (destruction, neutralization, capture, covering, fixation, etc.). The mission should be accompanied by the definition of operational metrics (“hard” and “soft”) through which mission accomplishment can be assessed. The definition of “hard” metrics does not eliminate the need for “soft” metrics, such as morale, the enemy’s willingness to fight, and support from the civilian population. Decisive defeat of terror army forces at the battalion/brigade level is certainly possible and is expressed by meeting clearly defined quantitative operational achievements, mainly related to territory and the operational capabilities of our forces (Biton, 2025; Col. G., 2025). Beyond this level, additional components – economic, social, and others – are required to decisively defeat the enemy system.

Fourth, the doctrine of the ground forces states that the IDF must strive to shorten the duration of the campaign due to the burden on the economy, which is reflected, among other things, in the reserve mobilization that forms the core of the IDF’s fighting manpower on land, and the serious threat to the home front (Ground Forces Headquarters, 2012, p. 17). The best way to do this is through the implementation of a maneuver approach in a campaign based on deception, which will dismantle the enemy system and will decisively defeat it quickly. While there is a real challenge in devising deception against hybrid terror armies, both at the beginning of the fighting and later against a disintegrating enemy system – as forces encountered in various fighting phases in Gaza – this challenge cannot be avoided.

It is worth asking whether the IDF succeeded in translating the principle of deception from the tactical level (where it achieved impressive successes) to the operational level in a way that dismantled the enemy system and shortened the war’s duration. Former Prime Minister Major General (res.) Ariel Sharon, perhaps the best field commander in IDF history, once criticized the transformation of the IDF from “an army whose power rests on qualitative factors and defeating the enemy through its collapse via deception; while here (becoming) an army that relies on quantitative superiority by ‘crushing’ the enemy through superior numbers” (Shimshi, 1995, p. 8). It appears that with regard to maneuver in Lebanon, Sharon’s statement is accurate and is highly relevant to maneuver in the Gaza Strip as well.

An IDF force fighting in the Gaza Strip during the "Iron Swords" War (Image by the IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

If we examine this in light of the various theaters, it is clear that in the Gaza Strip the campaign launched by the IDF in October 2023 is still ongoing. This is primarily due to the war objectives. Anyone versed in the art of war could have anticipated in advance (and indeed some senior IDF commanders assessed accordingly) that a campaign aimed at dismantling Hamas militarily and politically is a prolonged endeavor requiring substantial resources and forces over time. This raises the question: why did the IDF not concentrate a sufficiently large force for a maneuver that would simultaneously strike all enemy formations and centers in the central and southern parts of the Strip, in a manner that would surprise the enemy and shatter its systems? While it is understandable why such a move was not carried out at the beginning of the maneuver – an operation on a scale and intensity unseen by the IDF in years – why was it not done about two weeks later? Instead, the IDF continued to fight in a slow, firepower- and manpower-intensive manner – with forces not built to sustain such prolonged efforts. Alternatively, if a protracted campaign was anticipated, why was the force structure, particularly the reserve forces which were wasted extensively, not managed accordingly to avoid their attrition?

Another reason was the slower-than-required operational tempo, which allowed the enemy to recover. Initially, the IDF focused its efforts in northern Gaza, rather than simultaneously striking all enemy formations and centers in the central and southern areas. Even subsequently, the operational tempo was not sufficiently rapid and repeatedly allowed the enemy to regroup. This does not mean that tactical excellence did not yield cumulative achievements. During the war, IDF forces destroyed significant enemy assets, including tunnels, weapons depots, and command centers, and killed numerous enemy operatives, including senior commanders. The loss of these assets, alongside the pressure exerted on the population and Hamas’s loss of sovereignty in Gaza, are painful to the enemy and serve as a significant lever of pressure. However, the duration of the fighting indicates that the IDF struggled to generate a higher-level stratagem capable of rapidly dismantling the organization and thereby shortening the campaign. This stemmed, inter alia, from the enemy’s nature as a hybrid terror army – combining conventional military, terror, and guerrilla warfare – with less clear centers of gravity, as well as the necessity to consider the civilian population (which must be warned before combat entry), which undermined the ability to surprise.

The IDF succeeded in decisively defeating Hezbollah through an operational-level maneuver, albeit tactically the maneuver was rigid, predictable, heavy, and slow. In the Iranian theater, the IDF implemented a maneuver campaign with a decisive rationale, even reaching the brink of victory by itself (with the Americans providing the “additional push”); however, this was a campaign against a sovereign state and an industrial army, primarily based on airpower and covert operations, and cannot be equated with a campaign against a terror army.

Fifth, if it was clear that action in Iran required removal of the “Ring of Fire” in the first circle (Ortal, 2022, p. 43), why was the army not structured accordingly, the ground forces neglected, and the independence and initiative of field commanders impaired (Hazut, 2024, pp. 63, 112)? After all, a significant part of that threat removal depended on them, as indeed occurred. This raises questions regarding the size of the ground forces (and although it is preferable not to enlarge them disproportionately as was done post-Yom Kippur War, additional maneuvering combat formations are needed, or simply more manpower) as well as their capabilities. For example, why, in light of lessons from Operation “Protective Edge”, were infantry forces not prepared and trained in advance on a large scale for underground operations – an arena where much of the IDF’s advantages in intelligence and firepower cannot be realized? And why did IDF forces not fight in large numbers in tunnels at the start of the ground maneuver in Gaza? While this approach entails risk and requires daring and professional skill, it might have stunned Hamas, surprised it, and perhaps even contributed to its rapid defeat.

From all of the above it emerges that the ability to decisively defeat a terror army is possible. The goal of the maneuver approach (not necessarily ground maneuver) is to circumvent the enemy’s power factors and exploit vulnerabilities to bring about its rapid collapse. This can be done to a terror army, even relatively quickly, by an unexpected assault from multiple directions on all its systems. However, if the campaign’s objective is complete dismantlement, secondary and tertiary objectives can only be achieved in a prolonged campaign lasting a long time. Because after fighting the maneuvering forces, which are much stronger, the terror army will disintegrate into its basic form as terror cells. Then the army will be required to capture terror strongholds one by one, clear, raid, and maintain constant presence on the ground, as was done in the West Bank in “Defensive Shield” and afterward (Regev, 2025). This demands different preparations, including civilian campaign components aimed at driving a wedge between the population and terror. In any case, a mismatch between the objective and the resources allocated to it will inevitably lead to a less favorable outcome, as indeed occurred in the Gaza campaign. It is quite possible that with a different resource package the war objectives could have been achieved earlier. Since this is a “time-consuming” campaign, devouring manpower and additional resources (it is difficult to reach the last tunnel, the last terror stronghold, etc.), perhaps it is better to settle for more limited moves along the continuum between what the IDF has long termed in rounds of fighting as “severe damage” and Operation “Northern Arrows” – in which a terror army (Hezbollah) was defeated but not expelled or dismantled.

After all this, tactical decision has many faces and is not necessarily identical in all cases. However, one rule applies to all – where the military operation was well-prepared and there was high coordination between the resources allocated and the objectives, it reaped operational achievements, and where less so – this was reflected accordingly or exacted a higher cost in blood and money. It is incorrect to place the entire burden of decision solely on one branch or concept (the intelligence-strike complex or the Air Force); a balance in force construction is required to achieve optimization, whereby all of the IDF’s power components – including the ground forces – can contribute significantly to the enemy’s defeat. In summary, regarding ground combat, as stated by Brigadier General (res.) Guy Hazut, “Exploiting terrain, deceptive thinking, and learning the enemy’s weaknesses are the foundation of mastery in the art of war” (Hazut, 2024, p. 261).

Whether facing a terror army or an industrial military, the principle remains the same: achieving decisive victory on land requires adherence to these fundamental truths. Any attempt to bypass them – by relying solely on overwhelming firepower or deploying such a vast force that seemingly nothing could withstand it – while neglecting thorough terrain analysis, the design of a deception-based operational plan, and a deep understanding of the enemy’s vulnerabilities and nature, constitutes a violation of the profession of war.

The author thanks Major General (res.) Moti Baruch, Major General (res.) Yair Golan, Brigadier General (res.) Dr. Meir Finkel, Colonel (res.) Dvir Peleg, former MK Ofer Shelah, and Brigadier General (res.) Moshe (“Chico”) Tamir for their valuable comments on the article.

Bibliography:

- Amidror, Yaakov (May 2022). “Iran as a Military and Political Challenge to Israel.” Dado Center Journal, Issue 35, pp. 19–33. (Hebrew)

- Barnea, David “Dedi” (February 25, 2025). “Lecture by Mossad Director Dedi Barnea.” Annual INSS Conference 2025, Tel Aviv. (Hebrew)

- Ben-Yishai, Ron (October 10, 2024). "Report from the Village from Which Thousands of Redwan's Men Were to Rush into Israel." Ynet. (Hebrew)

- Ben-Yishai, Ron (December 12, 2024). "Lessons from 7/10 Implemented, Dangers Still in Syria and 5 Points Remaining to Decide Trump's Fate." Ynet. (Hebrew)

- Ben-Yishai, Ron (June 22, 2025). "Historic Safety Net and Striving for Conclusion." Ynet. (Hebrew)

- Baram, Amir & Perl Finkel, Gal (August 2021). "Northern Command – Tempering the Sword. Ma'arachot, Issue 491, pp. 8–15. (Hebrew)

- Bazak, Yuval & Gilat, Amir (June 24, 2024). Podcast "On Maneuver" (Episode 4). Ma'arachot. (Hebrew)

- Cohen, Gili (October 16, 2023). "Collapse of Hamas Rule and Solution for the Hostages Issue: The War Aims Document Revealed." Kan 11. (Hebrew)

- Col. G. (December 2024). "Terror Army – Character Traits." Ma'arachot, Issue 504, pp. 38–43. (Hebrew)

- Drucker, Raviv & Shelah, Ofer (2005). Boomerang. Keter. (Hebrew)

- Dvori, Nir (October 11, 2023). “Planned for About a Year: How Hamas's Surprise Attack Unfolded – Step by Step.” N12 News. (Hebrew)

- Eiland, Giora (2018). Autobiography. Yediot Sfarim. (Hebrew)

- Eizenkot, Gadi (June 2010). "Changing Threat? The Response in the Northern Arena." Military and Strategic Affairs, Vol. 2, Issue 1, pp. 23–32. (Hebrew)

- Finkel, Meir (November 2024). "Not ‘Their Own War’: Offensive Air Support for Maneuvering Forces in the ‘Iron Swords’ War in Gaza." Air & Defense, Issue 1, pp. 23–36. (Hebrew)

- Finkel, Meir (April 2025). “Military Decision in the ‘Iron Swords’ War: A Platform for Renewed Discussion.” Begin–Sadat Center for Strategic Studies (BESA). (Hebrew)

- Golan, Yair (June 30, 2019). Panel "Will Israel Win the Next War?" Herzliya Conference 2019, Reichman University. (Hebrew)

- Golan, Shimon (2013). A War on Yom Kippur: Decision Making at the High Command in the Yom Kippur War. Ma'arachot and Modan. (Hebrew)

- Goldfuss, Dan (March 13, 2024). "Statement by Commander of the Fire Brigade." Khan Yunis. (Hebrew)

- Ground Forces Command, (January 2012). Ground Forces Operations (Volume One – Introduction). Ground Forces, Land Forces Branch 3-ZI.6. (Hebrew)

- Harel, Amos & Issacharoff, Avi (2004). The Seventh War. Yedioth Books. (Hebrew)

- Hendel, Yoaz & Katz, Yaakov (2011). Israel vs. Iran. Kinneret, Zemora-Bitan. (Hebrew)

- Hazut, Guy (2024). The Hi-Tech Army and the Cavalry Army. Ma'arachot and Modan. (Hebrew)

- Hazut, Guy & Shelah, Ofer (September 30, 2024). "Land Maneuver on the Northern Front – Significance and Implications." INSS. (Hebrew)

- Ilanai, Itay (March 26, 2025). “The Tunnel Hunt, the Dramatic Escape, and the Long-Awaited Elimination: ‘This Is How We Killed Sinwar.’” Israel Hayom, Shishabat Supplement, pp. 22–33. (Hebrew)

- Kochavi, Aviv (December 25, 2019). "Lecture at IDF and Israeli Society Conference – In Memory of Lt.Gen. Amnon Lipkin-Shahak." Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya. (Hebrew)

- Kubovich, Yaniv (February 27, 2025). "IDF Investigation: Southern Command Did Not Expect Hamas to Invade; Gaza Division Defeated Quickly." Haaretz. (Hebrew)

- Kober, Avi (1996). Military Decision in the Israel-Arab Wars 1948-1982. Ma'arachot. (Hebrew)

- Levi, Shay (September 12, 2024). "IDF Officially Announces: 'We Defeated Hamas’s Rafah Brigade'." Mako. (Hebrew)

- Levi, Shay (January 9, 2025). "The IDF's Trap in Gaza and What Allows Terrorists to Resurge." Mako. (Hebrew)

- Mattis, Jim & West, Francis J. "Bing" (2022). Call Sign: Chaos. Ministry of Defense and Modan. (Hebrew)

- Mofaz, Shaul (2024). My Israeli Journey. Yedioth Books, Second Edition. (Hebrew)

- Ortal, Eran (May 2022). "Exhausting the Cat." Dado Center Journal, Issue 35, pp. 35–50.

- Peleg, Dvir (August 2023). Who is afraid of Multi-Front War?. Dado Center. (Hebrew)

- Regev, Liat (June 27, 2025). "Maj. Gen. (res.) Doron Almog: We Must Assume Hamas Always Wants to Attack and Be Ready." Kan 11, Reshet Bet. (Hebrew)

- Siboni, Gabi (October 2010). "Defeating Suicide Terrorism in Judea and Samaria 2002-2005". Military and Strategic Affairs, Vol. 2, Issue 2, pp. 95–104. (Hebrew)

- Simpkin, Richard (1999). Race to the Swift. Ma'arachot. (Hebrew)

- Shelah, Ofer (2003). The Israeli Army: A Radical Proposal. Kinneret, Zemora-Bitan, Dvir. (Hebrew)

- Shelah, Ofer (May 13, 2005). "I Work Without Any Warnings." Yedioth Ahronoth Weekend, pp. 8–9. (Hebrew)

- Shelah, Ofer (2015). Dare to Win. Yedioth Books. (Hebrew)

- Shimshi, Eliashiv (1995). By the Power of the stratagem. Ma'arachot. (Hebrew)

- Tamir, Moshe (August 2012). "Dilemmas in Fighting in Densely Populated Areas." Military and Strategic Affairs, Vol. 4, Issue 2, pp. 3–9. (Hebrew)

- Tovy, Tal (December 2009). “The Halakha Behind the Deed: The Theoretical Aspect of War Against Revolutionary Forces.” Military and Strategic Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 6–81. (Hebrew)

- Weiss, Efrat (July 5, 2007). “Outgoing Judea and Samaria Commander: Hamas Will Not Control the Sector.” Ynet. (Hebrew)

- Zaitun, Yoav (August 7, 2022). "The Heroic Battle of Egoz: Fighters Foiled Kidnapping of One Fallen Soldier – How IDF Prepared for the Threat." Ynet. (Hebrew)

- Zamir, Eyal (June 15, 2025). "Israeli Civilians – Whoever Harms You Pays and Will Pay a Heavy Price on Any Front." IDF Website. (Hebrew)

- Zohar, Guy (April 21, 2025). From the Other Side with Guy Zohar. Kan 11. (Hebrew)

Interviews

- Ashkenazi, Gabi (2024). Interview. (Hebrew)

- Biton, Ami (2025). Interview. (Hebrew)

- Colonel B. (2025). Interview. (Hebrew)

- Colonel (res.) G. (2025). Interview. (Hebrew)

- Finkelman, Yaron (2025). Interview. (Hebrew)

- Tamir, Moshe (2024). Interview. (Hebrew)